This relatively short, straightforward book fills a yawning gap in the J6 reportage. Who were the women? The dominant Deep State/media narrative is that white supremacist men, instigated by Donald Trump and QAnon, swarmed the Capitol on January 6, 2021, determined to reverse the outcome of the presidential election by fomenting insurrection.

Only the other day, a leftish Substacker of my acquaintance claimed, “only 1-2,000 women were at the Capitol,” but he failed to respond to the simple question, “how do you know?” and “are you distinguishing between the women on the Capitol grounds and the women in the Capitol building itself?” He didn’t respond, and I know why. This Administration and their media acolytes have no interest in showing that women were among the protesters, angered as much as their male counterparts by a country and an election gone wrong.

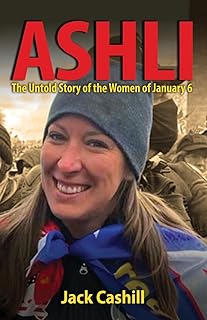

While most following the issue have probably heard of Ashli Babbitt, the Air Force veteran who was shot by the already-notorious Capitol Police officer Michael Byrd that day, very few seem to recall Rosanne Boyland. Boyland was already turning blue when she was pulled out of a deadly pile of protesters in the tunnel blackage that Capitol police had created. She might have lived, but for a Capitol Police officer named Lila Morris who beat her around the head with a tree branch. According to a witness, blood came out of Boyland’s nose, her left arm lifted and lowered, and she died. Her main protector was an African-American protester, whose presence, like other black Americans, the mainstream media will not acknowledge either. It does not fit the narrative.

Jack Cashill profiles eight women, including Boyland and Babbitt, who were at the Capitol. The others were a great grandmother who drove herself from Colorado to DC; an 18-year Marine Corps veteran; the lawyer/doctor daughter of Holocaust survivors who had already angered the establishment by publicly criticizing Covid vaccines and restrictions; a retired NYPD detective; a Cleveland school district therapist, and a registered nurse.

Their femaleness did not spare them the vindictive wrath of the Uniparty. At least one was betrayed by so-called friends. Even the women who walked into an open Capitol and did no more than pray or “admire the architecture” were sentenced to jail terms. Some are still awaiting sentencing this year. Most refused to plea bargain.

As most of you reading this already know, all the hundreds of protesters brought before DC juries were found guilty; two were acquitted in bench trials. A 57-year-old woman spent five days in an isolated cell with an open toilet with a male sex offender who claimed to be a woman. The doctor/lawyer was tried by a judge whose advances she had rebuffed while they were both students at Stanford Law. He did not recuse himself, and he no doubt enjoyed trying her boyfriend as well. The doctor says that her real crime was “betraying her social class.” Prosecutors in one woman’s case asked for an “upward” sentence above the guidelines because she had tried to hide her iphone from authorities and erased video footage. In 2016, Hillary Clinton and her attorneys had erased 30,000 emails, destroyed their devices with hammers, mocked her questioners, and faced no punishment. The anecdotes bring home in a way that abstractions cannot the huge injustices and cruelty visited on good citizens with patriotic motives. No BLM rioters, let alone Hilary Clinton, have faced anything resembling the penalties imposed on these otherwise law-abiding women.

A strength of this book is the time spent on the motivations of the women who came to the Capitol, some from across the country. They were alarmed by the decline in law and order that had reached a crescendo after the death of career criminal George Floyd. The imposition of unscientific and punitive Covid lockdowns galvanized them. “Abortion centers were open, but not churches. Celebrities and politicians could host parties, but not the average Joe.” The final straw was what they viewed as a tainted election and the suspiciously quick claim of victory by the left, whom Cashill calls “Jacobins.”

The women profiled represent a cross-section of normal America, including its struggles. Cashill notes the “uneven” lives his subjects had led, how they “traveled (on) roads riddled with speed bumps,” but which he says “made them more savvy than their cloistered feminist sisters…more willing to believe their own eyes and ears.” Roseanne Boyland had overcome addiction, which gave the DOJ an opportunity to claim that she had actually died of a fentanyl overdose. Others had turbulent or even violent childhoods or marriages. Not all were Trump supporters in 2016.

Another strength of the book is the stark evidence it draws of a double standard in the US justice system between the politically favored and unfavored. The women of January 6 were treated equally with the men in that regard.

The irony is that the posthumous defenders of George Floyd, who most likely had died of a fentanyl overdose, have ignored those inconvenient details from the record in the trials of the police officer who inadvertently killed him. The media also tried to tarnish the reputation of Ashli Babbitt, who had confronted her husband’s former girlfriend in a parking lot but who was a perfectly respectable business owner when she decided to go to Washington DC.

Julie Kelly’s “January 6” remains the best overall account of the riot and its aftermath. No one else has documented as fully the plot to provoke a powderkeg situation; reinforcements were spurned even as warnings of violence grew; and afterward important video evidence was withheld from the defense as part of a lawless frenzy to destroy the Jacobins’ political opposition. By showing these injustices through the experiences of his subjects, Cashill paints an important dimension to our understanding of that fateful day. Add this to your library while you can. (Bombardier Books, 2024)

Review by Paula Weiss