“Your history lies beneath your feet.”

A few years ago, my husband and I decided to finally pull up the broadloom carpet on our house’s main level. Imagine our pleasure in seeing the beautiful, narrow oak strips underneath, in almost perfect condition even after fifty years. We were intrigued when the floor finisher told us those oak strips had most likely come from a nearby mill, which consumed the trees that were felled to make way for our subdivision in the early 1960’s and then itself expired.

A slender book, “A Place Called Ilda: Race and Resilience at a Northern Virginia Crossroads,” by Tom Shoop (University of Virginia Press, 2024), served to remind me of what lies beneath the surface of our traffic-clogged Northern Virginia suburb. Ironically, the tiny African-American cemetery less than a mile away at one of our busiest intersections, Guinea Road and Little River Turnpike, becomes the racial fulcrum through which the author tells the story of Ilda over 150 years. Ultimately, the territorial clash between efficient commuting by the thousands of civil servants who moved to the area after WWII and the humble resting place led to the disinterment of the remains to a better cemetery down the street, which also has an interesting history. That’s Northern Virginia, where efficiency must triumph, but we do put up a historical marker at the bus stop.

In Virginia we treasure history, but often think of it as “what happened long before we got here,” as opposed to “something we relive and recreate every day.” Virginia history is stereotypically plantations, battlegrounds, and nowadays civil rights sites. This book peels back our surroundings, our musty carpet, to reveal our past. Yet this blue-voting area of Fairfax County acquired its virtue only recently, if you read Shoop’s account.

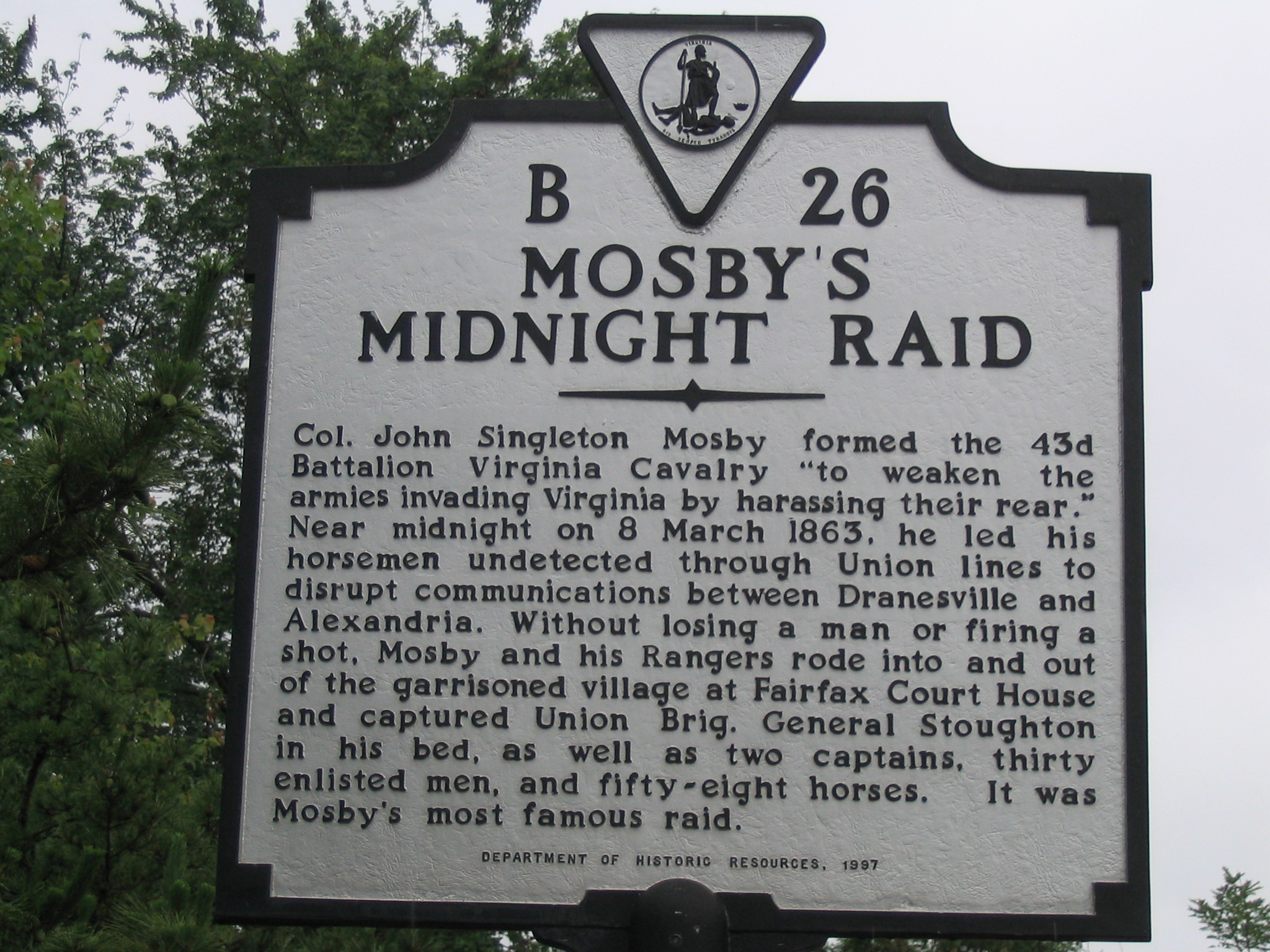

The African-American heritage of Ilda, a neighborhood just to the east of Fairfax City, is ironic given the relatively small percentage of black people today in this otherwise very ethnically diverse area. A plantation house two minutes’ drive away, now privately owned, gives tours once a year. A skirmish took place there in 1861, in which the Union soldiers received intelligence from a slave woman in the house. Even the name “Ilda” is said to derive from the nickname of a local African-American woman, Matilda Parker. During the war, LRT had been a no-man’s land between Federal-held Fairfax City and Washington to the east, with Mosby’s raiders taking a toll (see historical marker opposite the apartment complex). Mosby raided a Union contingent at Gooding’s Tavern, where the cemetery to which the Guinea Road cemetery’s inhabitants went was opened for all races and creeds in 1963. Outsiders came in and bought land and built houses. Whites and blacks lived side-by-side, although one is shocked in hindsight to read that while a school for white children was in the neighborhood, the black children had to walk three miles north to theirs (it is now the site of the popular Mosaic outdoor mall, to which none of us would ever consider walking). You learn that at the time of the Brown decision in 1954, there was no public high school for African Americans in Fairfax County. Black high schoolers traveled on their own dime to Washington DC, Arlington, or Manassas.

“A Place Called Ilda” documents the civil rights era in our neighborhood, to which thousands of civil servants had migrated in previous decades. It was not a placid transition, even if it was not Mississippi. The local high school resisted desegregation until 1965 (HT Woodson HS, named for the pro-segregation superintendent at the time, was recently re-named Carter Woodson HS, in honor of the eminent black historian who was born in Virginia but whose main qualification seems to have been that he was also named Woodson). Northern Virginia efficiency again.

But few of us living here really give thought to the history, or to how our neighborhood evolved. It is a shock reading this book when the author discusses the new Japanese restaurant (c. 2020) and the Jewish Community Center across LRT from the cemetery that was founded in 1980, as if they are too part of the history. I learned it had first been a Christian school. My husband still remembers attending meetings in the original building, a dilapidated white house. But the JCC promised Fairfax County it would not destroy the house, and so it has become a cultural center adjacent to the main brick JCC that was built in 1990.

We are reminded of history when we notice that the larger properties along LRT that were here first tend to have a higher percentage of campaign signs for Republicans. The home with the sign “Dr. John Forest,” long known for its uncompromising right-wing signage, during this last campaign displayed a pickup truck adorned with giant Trump signs that has now been replaced by a simple “God Blessed America.” Dr. Forest is mentioned in the book too; he bought that property in 1977 for a home dental practice, and in the process tore down the Ilda Church that was the last “pillar” of the old neighborhood. He is still feisty, it seems. So he is history, and yet he is here too. I also learned that in the 1870s, Ilda Church adhered fiercely to the Lost Cause theology, and its pastor was a veteran of Mosby’s raiders. A short distance away is Wakefield Chapel, patronized by Union veterans and abolitionists. One current resident, told in 1976 that his grandfather had been the pastor at the Northern-leaning church, said, “I was a little disappointed.” I drive by lovely Wakefield Chapel, no longer used for services, whenever I am avoiding a traffic jam on LRT.

As a conservative, it gives me joy to connect with our local history, as much as it did to rip up the suburban carpeting and see the oak floors beneath. Is it proud history? Yes and no, but that’s always the nature of history, and it explains—encouragingly—why the present is never the same as the past. Some would say, you’re from New York, it isn’t even your history. But that’s a presentism influenced heavily by the poisonous DEI/intersectionality agenda. By that logic, my history should only be the Temple in Jerusalem and the shtetls of Eastern Europe, even though I have lived far longer in Virginia than in New York and never in those other places. Your history lies beneath your feet as well as in your genes.

Conservatives seem more interested in and respectful of history than are liberals, who often twist it to suit a presentist agenda. We will take it at face value. Perhaps part of our respect is because, in the tradition of Burke and de Tocqueville, the little platoons or the town hall meeting that belong to a very small locality are the entities primarily responsible for civilization and good governance. Perhaps it is because we respect the common sense and wisdom of the past over untested modern fetishes. Conservatives are by nature suspicious of state infringement into private and local spheres because of its homogenizing and tyrannizing consequences. As theorist Michael Oakeshott said, “to be a conservative is to prefer the familiar to the unknown, the tried to the untried…the near to the distant.” It is comforting to know we have history around us.

“A Place Called Ilda” reassures us that even modern Americans need not be rootless, that history surrounds us even amid shopping plazas and relentless traffic. I have not seen my neighborhood with the same eyes since reading this book. My New Year’s resolution is now to read every one of the 75 historical markers in Fairfax County. To know your home is to know yourself.

Paula Weiss is the author of The Antifan Girlfriend and The Deplorable Underground.